Jan 15, 2026

Why the Future of Financial Crime Prevention Is Collaborative

Why the Future of Financial Crime Prevention Is Collaborative

Why the Future of Financial Crime Prevention Is Collaborative

Financial institutions need a more connected, intelligence-driven approach to keep pace with highly networked criminal groups. This begins by acknowledging why current structures fail, and how technology and regulatory evolution can help unlock a path forward

Author

Chris Anderson, Managing Partner, CubeMatch

TABLE OF CONTENTS

See Less

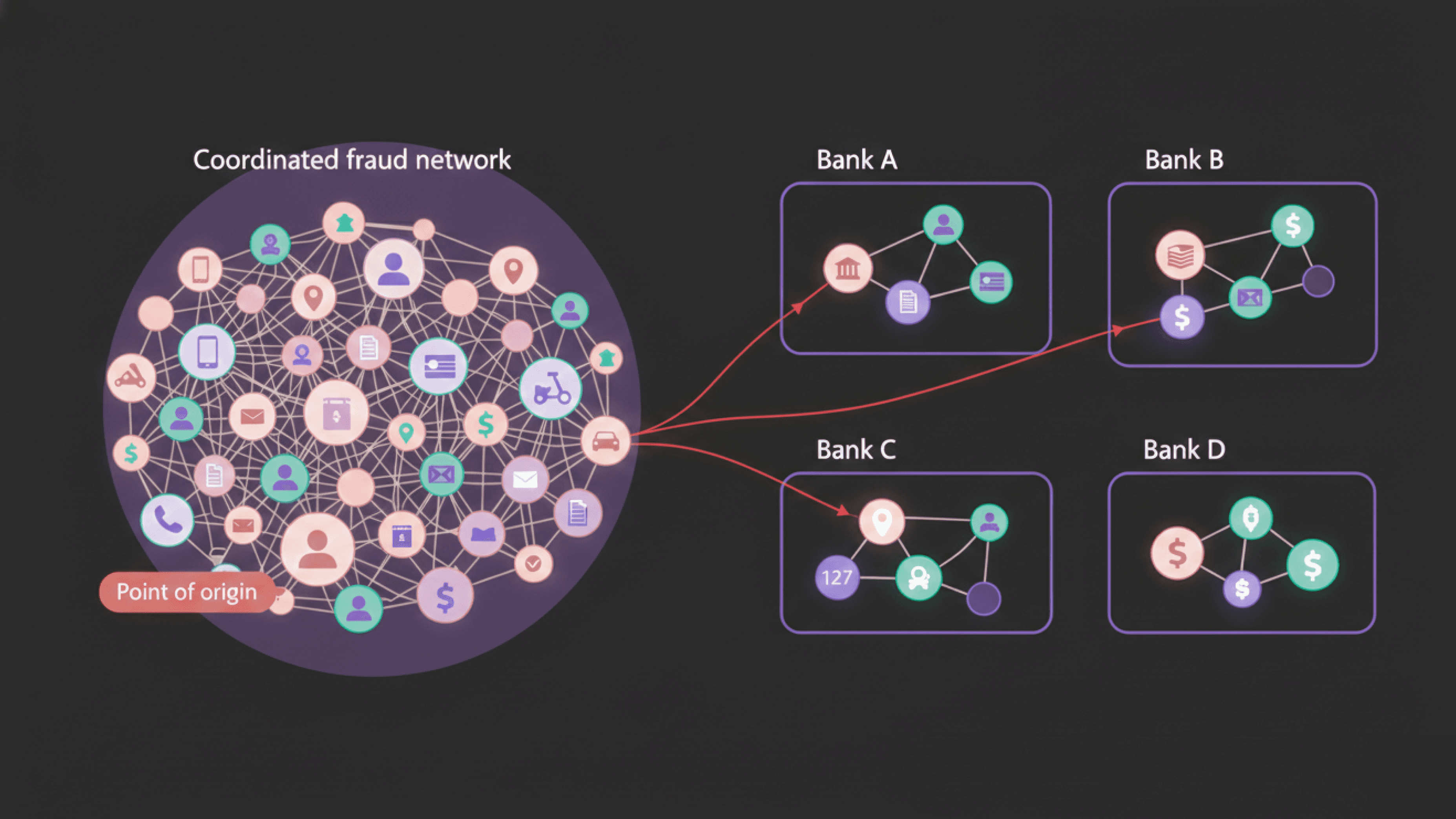

Financial crime is evolving at an unprecedented pace. Despite investments in monitoring systems, compliance frameworks, and investigative resources, fraud networks continue to operate with extraordinary coordination and agility. Their advantage is simple: collaboration; while financial institutions often remain siloed.

According to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), collaboration through information sharing is one of the central pillars of a strong AML framework. Yet across the private sector, it remains limited, fragmented, or non-existent, leading to siloed actions.

Historical processes, restrictive interpretations of data protection laws, and outdated technology keep financial institutions trapped with outdated investigative models.

Fragmentation leads to failure

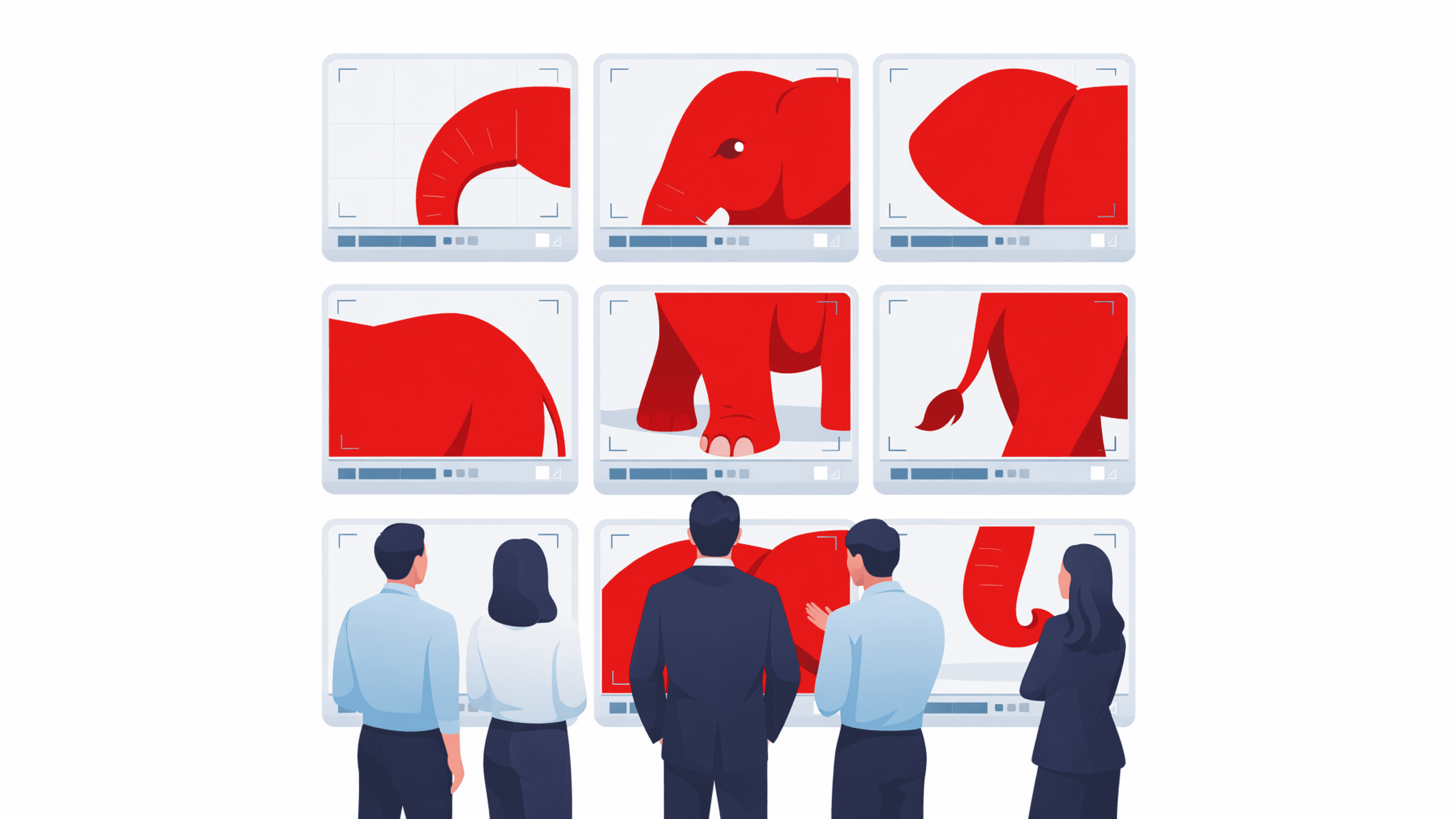

The Financial Crime Compliance (FCC) model, developed over the decades, is based on legacy operational procedures, confidentiality philosophies, and business structures. All these factors have resulted in the creation of siloed business units, such as AML, CTF, sanctions, and fraud. Each of these silos operate independently of the others. They have their own systems, frameworks, and reporting processes to investigate financial crime.

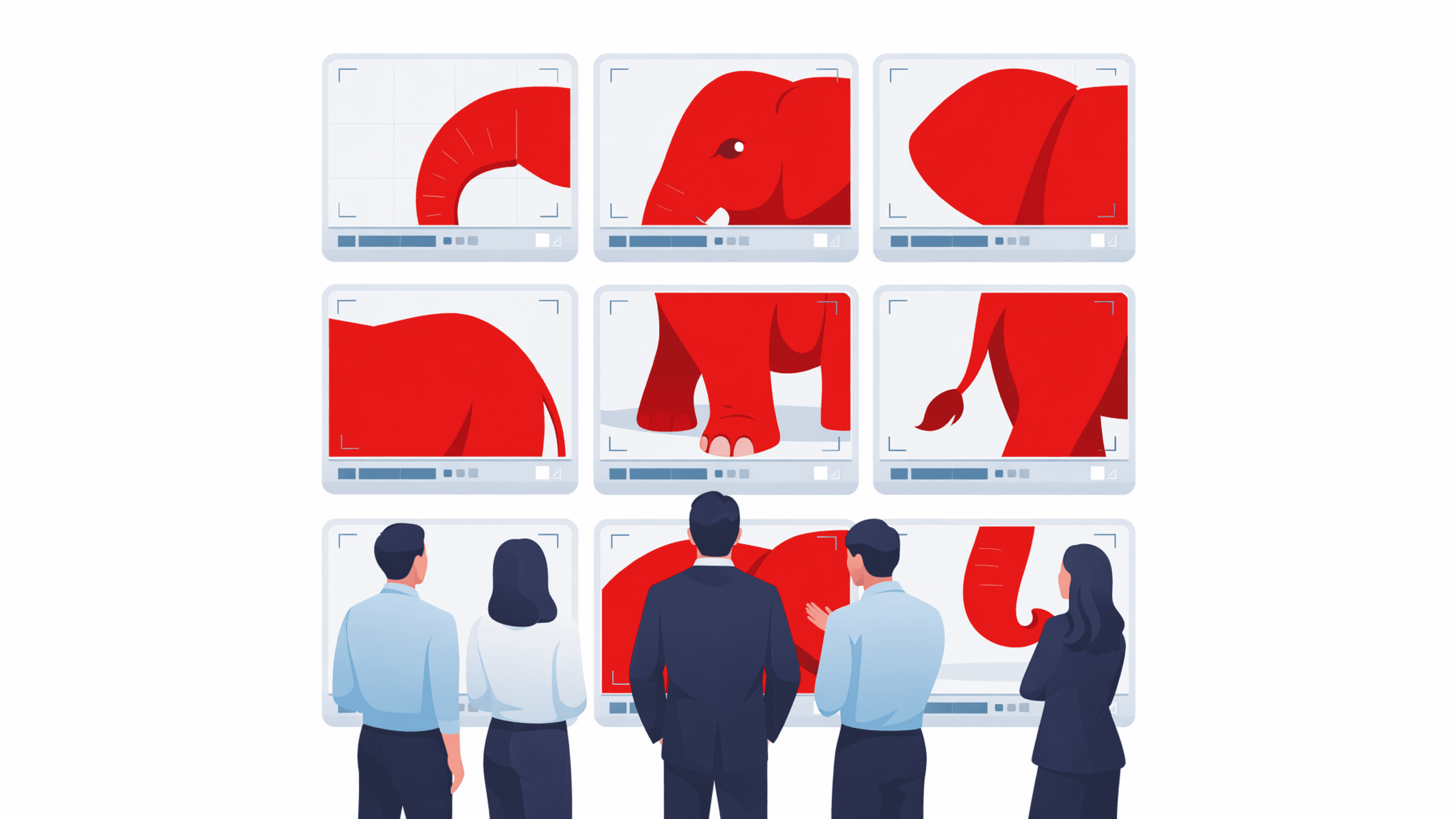

In the absence of multi-unit visibility across business lines, a financial institution can only detect the symptoms instead of the patterns. This results in missing the overall fraud picture and multiple financial crime investigations occurring in parallel; without any interaction.

While the overall goal of the FCC model was to improve expertise and operational efficiency within the units, it has created more challenges than opportunities.

For instance, it becomes difficult to identify the interconnected nature of complex financial crimes where fraudsters operate several scams using:

independent accounts, spread across business units

synthetic identities to feed mule networks

cross-border fraud to fund terrorism

trade-based schemes to evade sanctions

To understand how silos have become entrenched in the FCC, it is essential to analyze the constraints that prevent financial institutions from collaborating in their fraud prevention efforts.

Constraints in internal sharing and collaboration

There are several barriers that impact how well businesses can exchange and use internal knowledge, creating an environment where collaboration is viewed as risky, complicated, or difficult to manage. The top three being:

Old systems: Large enterprises usually have multiple systems built across many different platforms from acquisitions and expansions over the years. These systems do not link together or communicate with one another. As a result, investigators must reconcile disparate systems of information to be able to gain an accurate view of what happened in each instance. Many financial crime investigators feel fragmented systems are an impediment to effective intelligence sharing.

Different approaches: Global policies usually evolve into a business’s regional or business-specific procedures. Depending on how these are interpreted, they result in several different levels of investigative rigors.

Regulatory over-interpretations: Variations in regulatory scrutiny and interpretation can create hesitation in sharing information, even when it is allowed. This can create confusion and impede collective investigative efforts.

Regulatory and cross-border constraints

Financial crime regulations stem from global standards. However, they are often interpreted differently across jurisdictions. By the time FATF principles filter into regional directives, national laws, regulatory guidance, and internal policy, financial institutions have faced a patchwork of expectations.

The data protection paradox further aggravates the situation. Cross-border data protection frameworks, namely: GDPR, regional privacy laws, sector-specific obligations, are often viewed as barriers to collaboration.

Financial institutions worry that sharing too much can expose them to penalties.

On the contrary, government guidance in multiple jurisdictions, including the UK, emphasizes just the opposite: group-wide and cross-border information sharing is essential to managing money laundering and terrorist financing risks.

The real challenge, therefore, is perception, not regulation.

Centralize and elevate intelligence

Given the complexity of today’s threat landscape, financial institutions must rethink their investigative and intelligence architecture. As criminals exploit jurisdictional inconsistencies, it is imperative that financial institutions question the cost of inaction.

The way forward involves consolidation and centralizing the intelligence repository.

With a shared internal platform, financial institutions can bridge fragmented systems and teams by:

Ingesting multiple formats and data sources

Identifying commonalities between open and historical cases

Eliminating duplication

Facilitating controlled, permission-based access

Supporting escalations across AML, fraud, sanctions, and other FCC domains

This approach does not require a massive IT overhaul. However, by creating a system-agnostic repository, it makes legacy infrastructures inter-operable while still enabling investigators to view the connections that matter.

Collaboration across the ecosystem

Because fraudsters collaborate across networks, not just within them; internal consolidation alone is not enough. Financial institutions must look to collaborate in the following ways:

Public-private cooperation: Over the last decade, there has been an important shift with public-private cooperation becoming mainstream in many advanced democracies. This development has helped improve SAR quality, enriched intelligence, and enabled proactive and better understanding of emerging risks.

However, the percentage of public-private sharing remains minimal, which pulls financial institutions one step behind. On the other hand, fraud networks exploit fintechs, telecoms, social media platforms, eCommerce marketplaces, and traditional banks, simultaneously.

Private-private intelligence sharing: Global regulators increasingly recognize that financial crime cannot be contained without structured collaboration among private-sector institutions. For instance, legislative reforms, such as those underpinning Singapore’s COSMIC platform and the UK’s Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act (ECCTA), signal a global shift which is directing the industry to move from possibility to inevitability. These reforms help:

Remove legal ambiguity

Provide safe passage for institutions wishing to share intelligence

Introduce protections against liability

Encourage (and may eventually require) controlled intelligence sharing

Related Read: It Takes a Network to Fight a Network: Inside the Bureau Fraud Forum

De-risking collaboration with privacy technology

Legal changes are on the horizon for many countries, and technology will become the primary tool for collaborating while keeping information private.

Privacy Enhancing Technology (PET), developed through recent advancements, allows for collaboration without disclosing confidential information.

Built with a multi-tenant architecture, several technologies under this broad category allow each tenant/business to maintain exclusive control of their sensitive data, while providing support for the following functions:

Event and entity connection detection

Match surface across institutions

Elevate matched cases to a shared cloud where agreement to share intelligence has been established by the data owners.

Allow for anonymization of data, if required

Provide governance and audit capability

The PET model is sector-agnostic, scalable, and approved by the Federal government.

It removes legal and operational barriers, providing businesses with the confidence that they can collaborate while continuing to comply with current and future regulations.

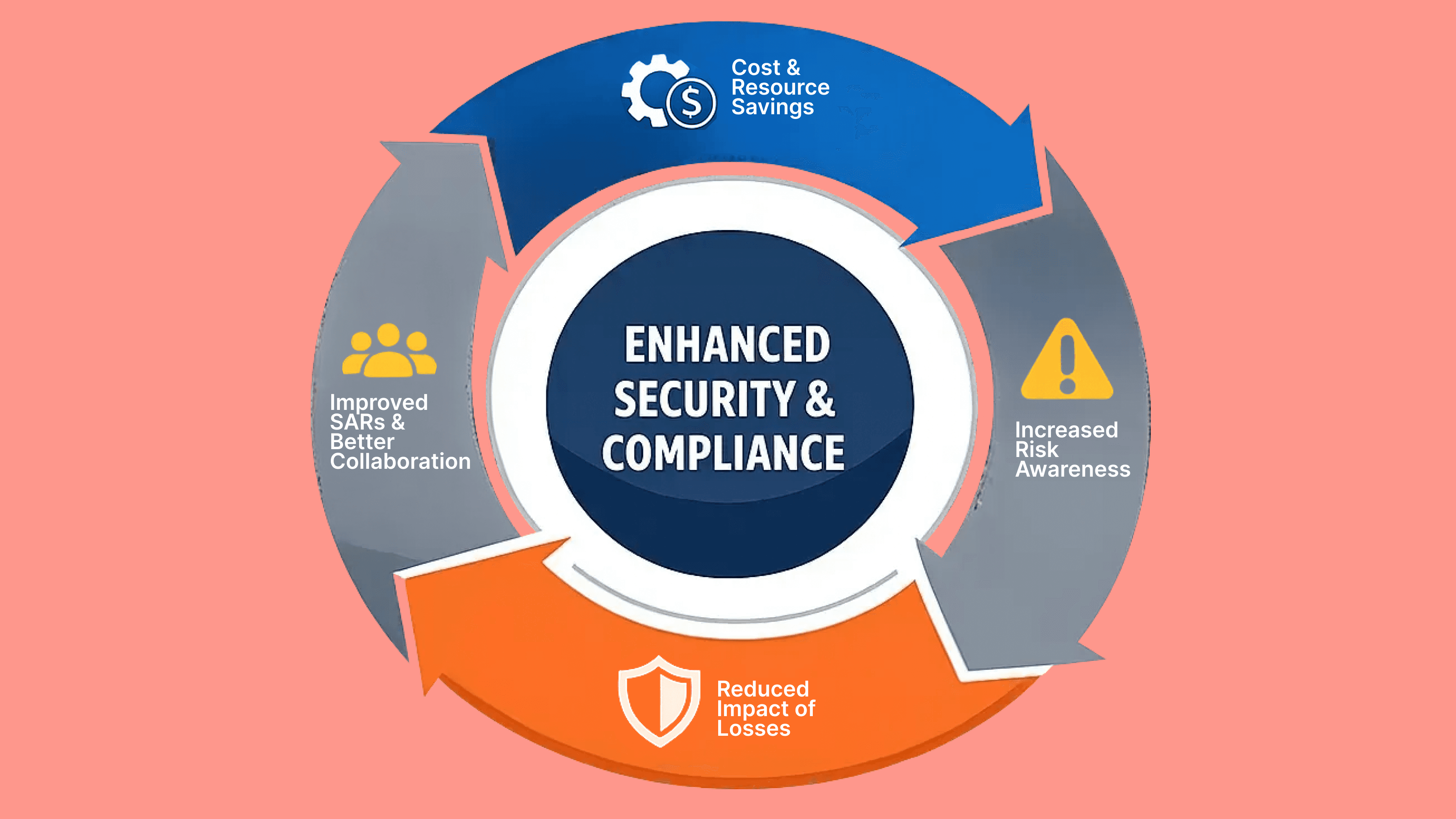

The benefits of intelligence sharing

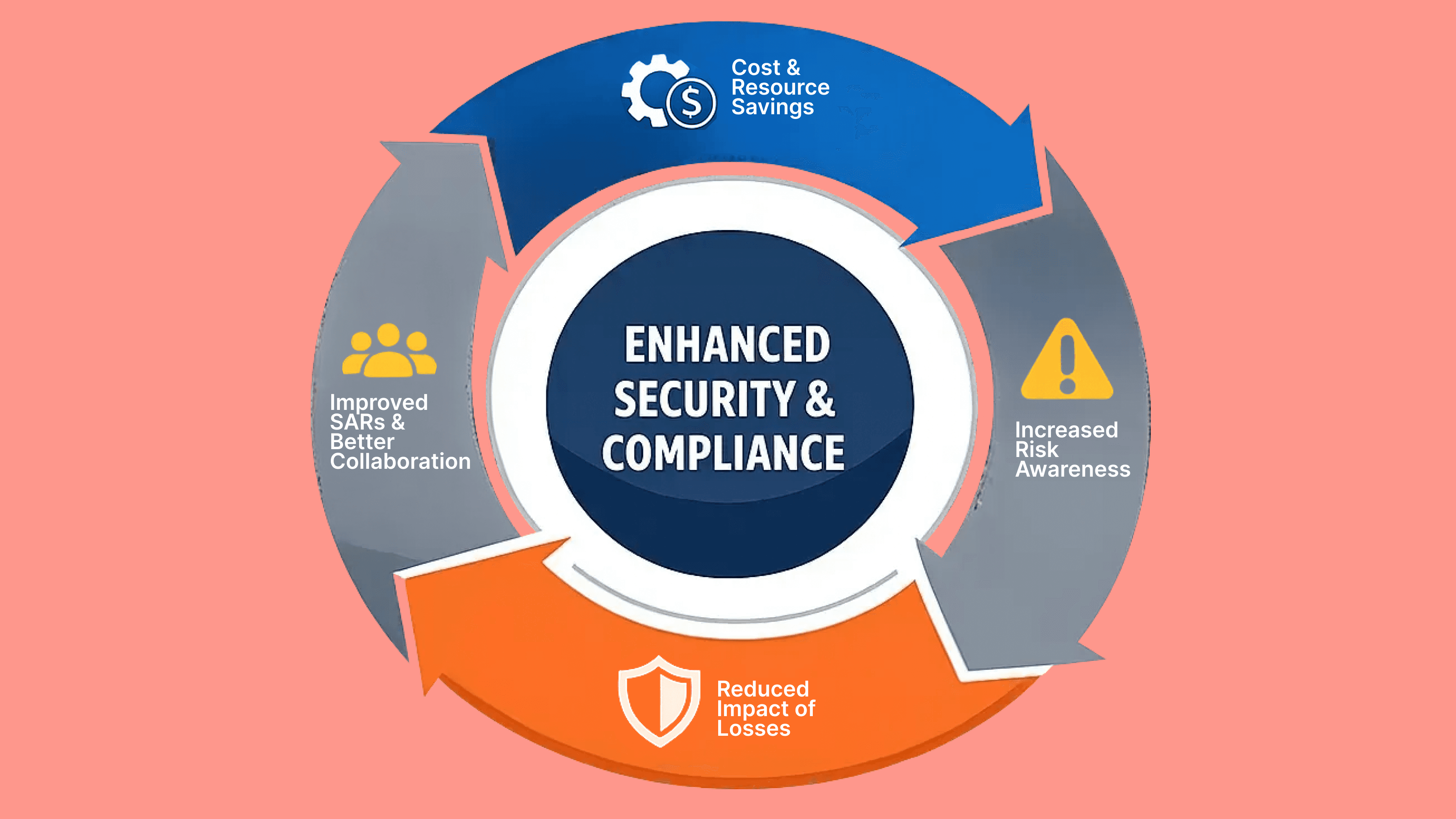

Effective intelligence sharing across businesses and other entities promises several benefits. These include:

Cost and resource savings: By streamlining the investigative process and eliminating redundancy, businesses can reduce the time and effort spent on manual investigations. This frees up resources for more complex and unique investigations.

Increased risk awareness: By employing a comprehensive review of intelligence, a business can better identify risk indicators and trends associated with their operations, and align their portfolio to the specified risk appetite.

Reduced impact of losses: With improved capabilities to minimize financial or reputation loss, businesses can reduce the instances of fraud and, therefore, reputational harm.

Improved SARs and better collaboration: Providing law enforcement with a better class of actionable intelligence results in fewer SARs, but higher value per report. This collaboration also increases the probability of success for all involved parties and helps create a more resilient financial services sector.

Final thoughts: Fighting a network needs a networked approach

Financial crime has always been a networked problem. Therefore, to successfully combat it, financial institutions must collaborate. They must use shared intelligence, coordinate actions, and ultimately break the barriers that have been holding back efforts to deter and fight financial crime.

The Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act (ECCTA) is a catalyst for change, providing financial institutions with an opportunity to share threat intelligence across the AML-regulated sector and increase cooperation.

In response, financial institutions must consolidate their internal resources and information related to financial crime, and create a legal framework for sharing information with their peers. This will help improve customer experience, reduce operational costs, increase safety of all financial institutions, and strengthen resilience of the overall financial system.

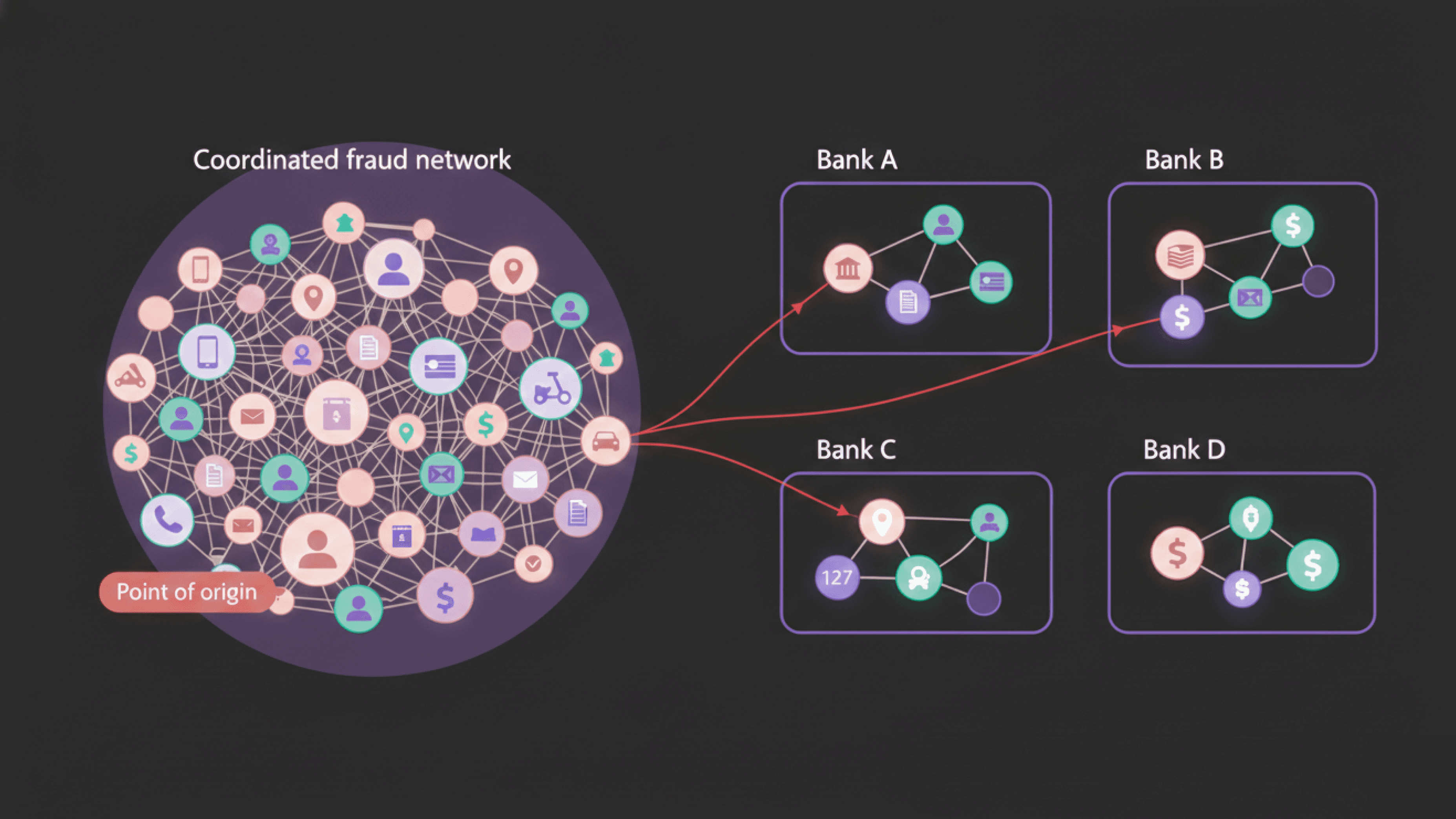

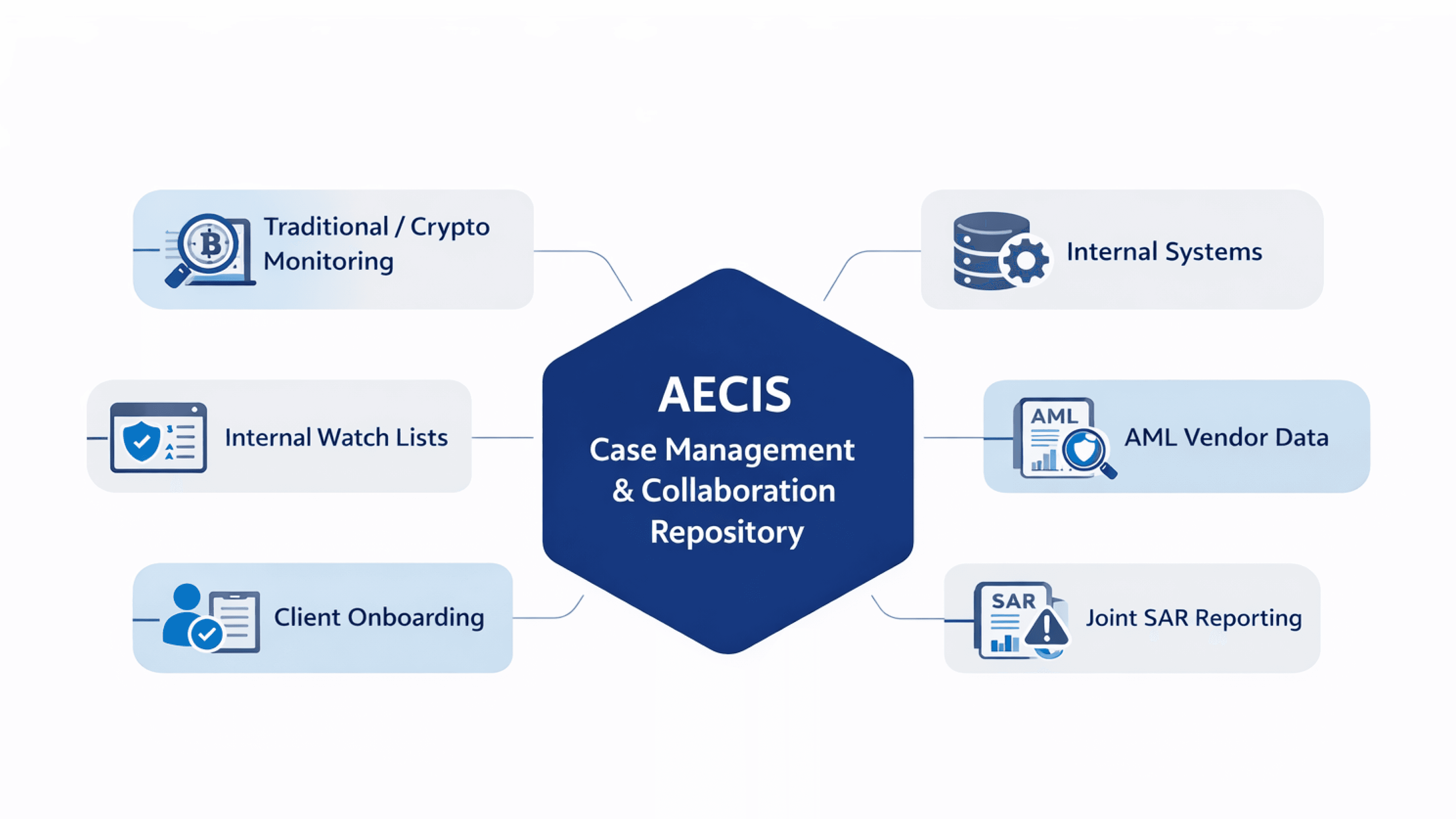

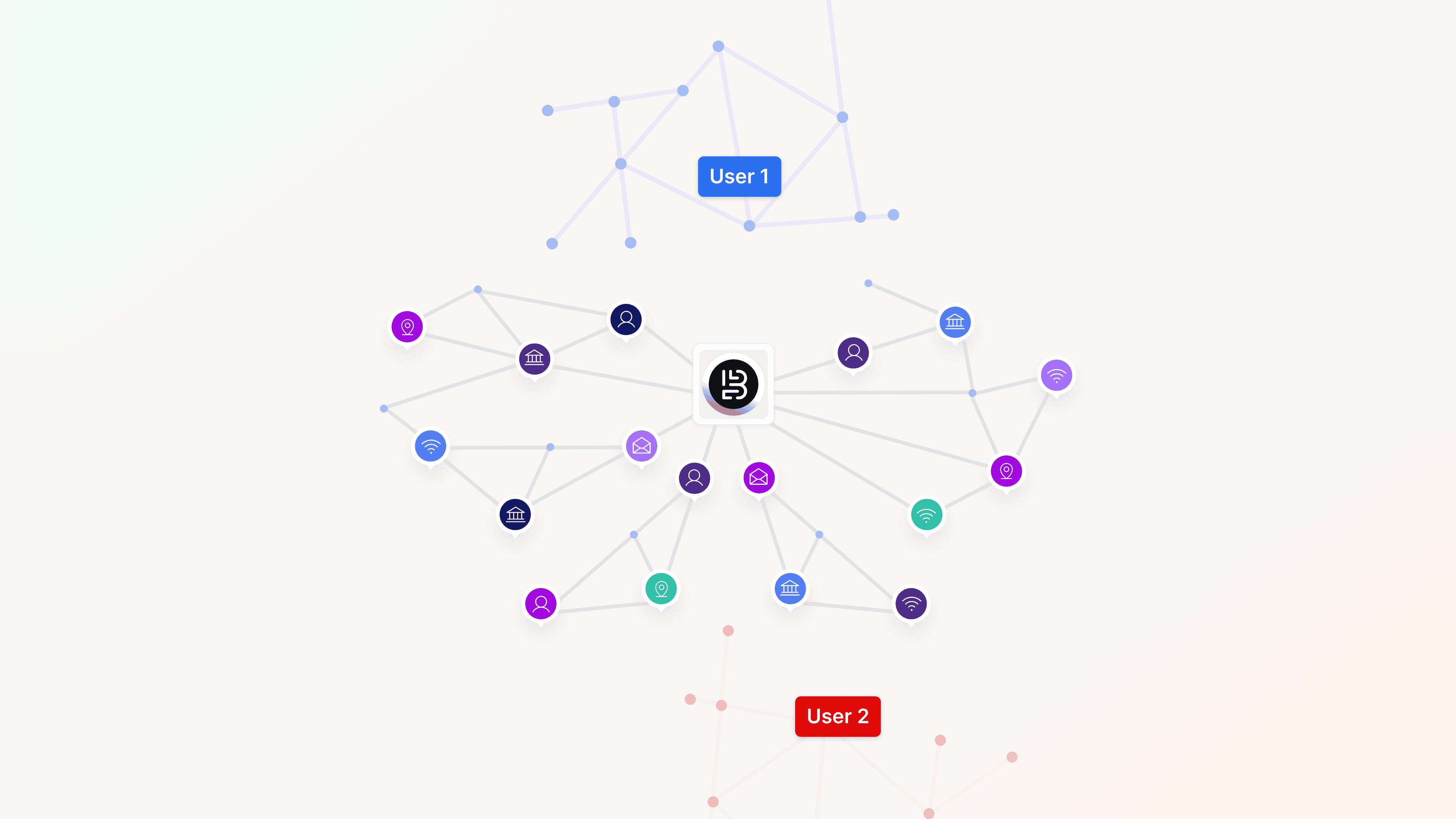

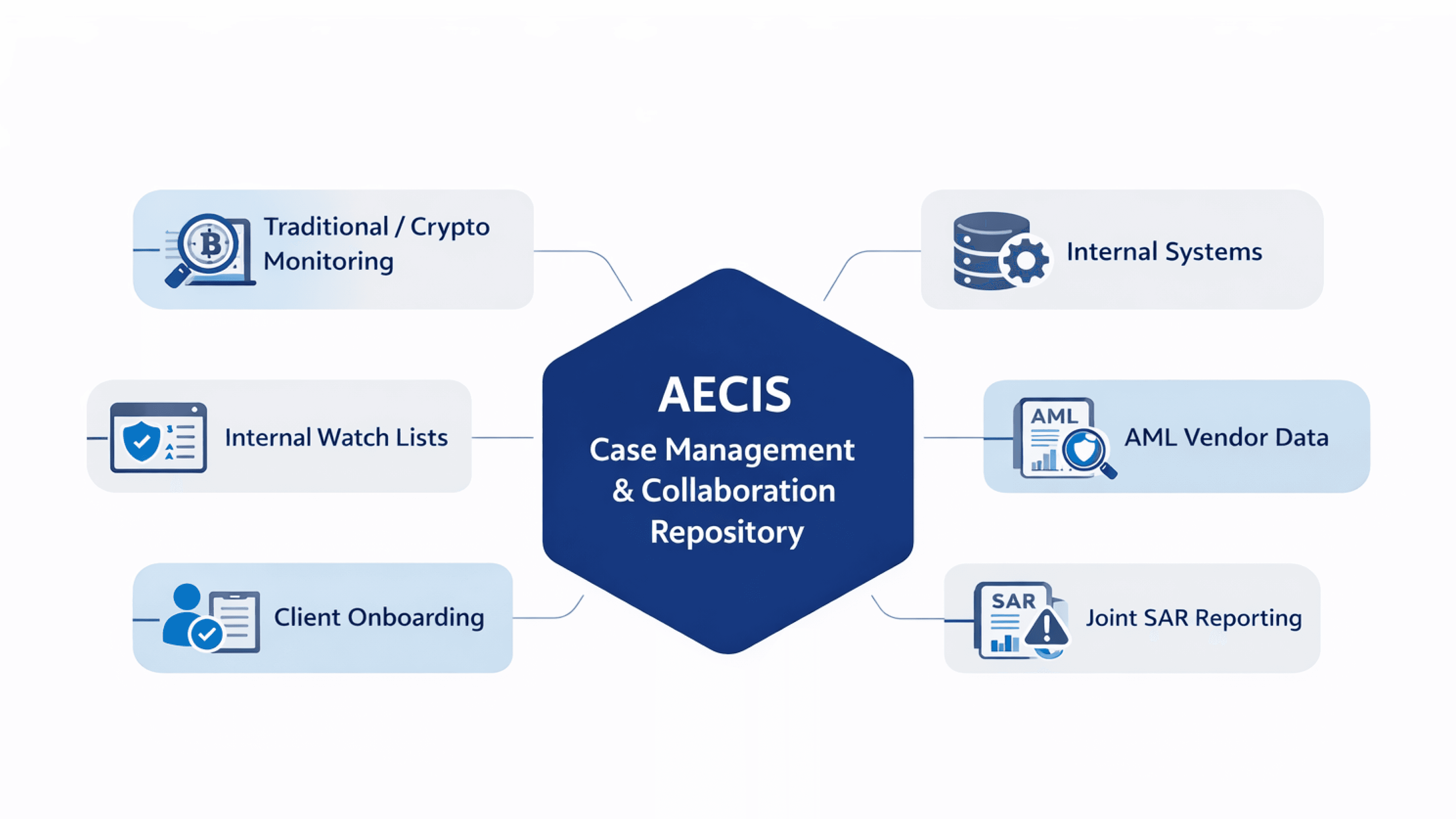

Bureau’s Graph Identity Network (GIN) and CubeMatch’s AECIS enable financial institutions to connect entities, accounts, devices, behaviors, and risk signals from across organizations and departments. This ability to detect patterns and uncover hidden networks in real time enhances fraud detection from individual incidents to identifying coordinated threats, while also maintaining privacy and compliance with regulations.

See how networked intelligence can reduce risk and cost; reach out to me or an expert at Bureau today.

Financial crime is evolving at an unprecedented pace. Despite investments in monitoring systems, compliance frameworks, and investigative resources, fraud networks continue to operate with extraordinary coordination and agility. Their advantage is simple: collaboration; while financial institutions often remain siloed.

According to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), collaboration through information sharing is one of the central pillars of a strong AML framework. Yet across the private sector, it remains limited, fragmented, or non-existent, leading to siloed actions.

Historical processes, restrictive interpretations of data protection laws, and outdated technology keep financial institutions trapped with outdated investigative models.

Fragmentation leads to failure

The Financial Crime Compliance (FCC) model, developed over the decades, is based on legacy operational procedures, confidentiality philosophies, and business structures. All these factors have resulted in the creation of siloed business units, such as AML, CTF, sanctions, and fraud. Each of these silos operate independently of the others. They have their own systems, frameworks, and reporting processes to investigate financial crime.

In the absence of multi-unit visibility across business lines, a financial institution can only detect the symptoms instead of the patterns. This results in missing the overall fraud picture and multiple financial crime investigations occurring in parallel; without any interaction.

While the overall goal of the FCC model was to improve expertise and operational efficiency within the units, it has created more challenges than opportunities.

For instance, it becomes difficult to identify the interconnected nature of complex financial crimes where fraudsters operate several scams using:

independent accounts, spread across business units

synthetic identities to feed mule networks

cross-border fraud to fund terrorism

trade-based schemes to evade sanctions

To understand how silos have become entrenched in the FCC, it is essential to analyze the constraints that prevent financial institutions from collaborating in their fraud prevention efforts.

Constraints in internal sharing and collaboration

There are several barriers that impact how well businesses can exchange and use internal knowledge, creating an environment where collaboration is viewed as risky, complicated, or difficult to manage. The top three being:

Old systems: Large enterprises usually have multiple systems built across many different platforms from acquisitions and expansions over the years. These systems do not link together or communicate with one another. As a result, investigators must reconcile disparate systems of information to be able to gain an accurate view of what happened in each instance. Many financial crime investigators feel fragmented systems are an impediment to effective intelligence sharing.

Different approaches: Global policies usually evolve into a business’s regional or business-specific procedures. Depending on how these are interpreted, they result in several different levels of investigative rigors.

Regulatory over-interpretations: Variations in regulatory scrutiny and interpretation can create hesitation in sharing information, even when it is allowed. This can create confusion and impede collective investigative efforts.

Regulatory and cross-border constraints

Financial crime regulations stem from global standards. However, they are often interpreted differently across jurisdictions. By the time FATF principles filter into regional directives, national laws, regulatory guidance, and internal policy, financial institutions have faced a patchwork of expectations.

The data protection paradox further aggravates the situation. Cross-border data protection frameworks, namely: GDPR, regional privacy laws, sector-specific obligations, are often viewed as barriers to collaboration.

Financial institutions worry that sharing too much can expose them to penalties.

On the contrary, government guidance in multiple jurisdictions, including the UK, emphasizes just the opposite: group-wide and cross-border information sharing is essential to managing money laundering and terrorist financing risks.

The real challenge, therefore, is perception, not regulation.

Centralize and elevate intelligence

Given the complexity of today’s threat landscape, financial institutions must rethink their investigative and intelligence architecture. As criminals exploit jurisdictional inconsistencies, it is imperative that financial institutions question the cost of inaction.

The way forward involves consolidation and centralizing the intelligence repository.

With a shared internal platform, financial institutions can bridge fragmented systems and teams by:

Ingesting multiple formats and data sources

Identifying commonalities between open and historical cases

Eliminating duplication

Facilitating controlled, permission-based access

Supporting escalations across AML, fraud, sanctions, and other FCC domains

This approach does not require a massive IT overhaul. However, by creating a system-agnostic repository, it makes legacy infrastructures inter-operable while still enabling investigators to view the connections that matter.

Collaboration across the ecosystem

Because fraudsters collaborate across networks, not just within them; internal consolidation alone is not enough. Financial institutions must look to collaborate in the following ways:

Public-private cooperation: Over the last decade, there has been an important shift with public-private cooperation becoming mainstream in many advanced democracies. This development has helped improve SAR quality, enriched intelligence, and enabled proactive and better understanding of emerging risks.

However, the percentage of public-private sharing remains minimal, which pulls financial institutions one step behind. On the other hand, fraud networks exploit fintechs, telecoms, social media platforms, eCommerce marketplaces, and traditional banks, simultaneously.

Private-private intelligence sharing: Global regulators increasingly recognize that financial crime cannot be contained without structured collaboration among private-sector institutions. For instance, legislative reforms, such as those underpinning Singapore’s COSMIC platform and the UK’s Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act (ECCTA), signal a global shift which is directing the industry to move from possibility to inevitability. These reforms help:

Remove legal ambiguity

Provide safe passage for institutions wishing to share intelligence

Introduce protections against liability

Encourage (and may eventually require) controlled intelligence sharing

Related Read: It Takes a Network to Fight a Network: Inside the Bureau Fraud Forum

De-risking collaboration with privacy technology

Legal changes are on the horizon for many countries, and technology will become the primary tool for collaborating while keeping information private.

Privacy Enhancing Technology (PET), developed through recent advancements, allows for collaboration without disclosing confidential information.

Built with a multi-tenant architecture, several technologies under this broad category allow each tenant/business to maintain exclusive control of their sensitive data, while providing support for the following functions:

Event and entity connection detection

Match surface across institutions

Elevate matched cases to a shared cloud where agreement to share intelligence has been established by the data owners.

Allow for anonymization of data, if required

Provide governance and audit capability

The PET model is sector-agnostic, scalable, and approved by the Federal government.

It removes legal and operational barriers, providing businesses with the confidence that they can collaborate while continuing to comply with current and future regulations.

The benefits of intelligence sharing

Effective intelligence sharing across businesses and other entities promises several benefits. These include:

Cost and resource savings: By streamlining the investigative process and eliminating redundancy, businesses can reduce the time and effort spent on manual investigations. This frees up resources for more complex and unique investigations.

Increased risk awareness: By employing a comprehensive review of intelligence, a business can better identify risk indicators and trends associated with their operations, and align their portfolio to the specified risk appetite.

Reduced impact of losses: With improved capabilities to minimize financial or reputation loss, businesses can reduce the instances of fraud and, therefore, reputational harm.

Improved SARs and better collaboration: Providing law enforcement with a better class of actionable intelligence results in fewer SARs, but higher value per report. This collaboration also increases the probability of success for all involved parties and helps create a more resilient financial services sector.

Final thoughts: Fighting a network needs a networked approach

Financial crime has always been a networked problem. Therefore, to successfully combat it, financial institutions must collaborate. They must use shared intelligence, coordinate actions, and ultimately break the barriers that have been holding back efforts to deter and fight financial crime.

The Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act (ECCTA) is a catalyst for change, providing financial institutions with an opportunity to share threat intelligence across the AML-regulated sector and increase cooperation.

In response, financial institutions must consolidate their internal resources and information related to financial crime, and create a legal framework for sharing information with their peers. This will help improve customer experience, reduce operational costs, increase safety of all financial institutions, and strengthen resilience of the overall financial system.

Bureau’s Graph Identity Network (GIN) and CubeMatch’s AECIS enable financial institutions to connect entities, accounts, devices, behaviors, and risk signals from across organizations and departments. This ability to detect patterns and uncover hidden networks in real time enhances fraud detection from individual incidents to identifying coordinated threats, while also maintaining privacy and compliance with regulations.

See how networked intelligence can reduce risk and cost; reach out to me or an expert at Bureau today.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

See More

TABLE OF CONTENTS

See More

Recommended Blogs

How Middle East Banks Can Rethink Fraud Prevention

Rapid digital adoption is reshaping banking across the Middle East. Instant onboarding, digital wallets, and super apps are now the norm, expanding the attack surface in the process. To deliver strong protection without adding friction, banks in the region must counter AI-driven fraud with connected intelligence across identity, devices, and behavior.

Building Real-time Defenses in an Always-on Economy

In an always-on, connected economy, risks are created in real-time, rather than at discrete checkpoints. Defense strategies must, accordingly, level up to measure trust throughout the entire user experience, from first interaction to every single transaction. This always-on protection needs connected signals, adaptive decisioning, and protection that can keep pace with evolving digital behaviors and access methods.

iGaming KYC: Balancing Risk, Compliance, and Player Experience

KYC-driven identity verification is a core element for fraud prevention in iGaming. It helps these platforms establish trust at onboarding by creating a secure, fair, and sustainable ecosystem, preventing abuse, preserving integrity of the platform, and ensuring regulatory compliance.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

See Less

TABLE OF CONTENTS

See Less

Solutions

Resources

© 2026 Bureau . All rights reserved.

Solutions

Solutions

Industries

Industries

Resources

Resources

Company

Company

Solutions

Solutions

Industries

Industries

Resources

Resources

Company

Company

© 2025 Bureau . All rights reserved. Privacy Policy. Terms of Service.

© 2025 Bureau . All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy. Terms of Service.

Follow Us

Leave behind fragmented tools. Stop fraud rings, cut false declines, and deliver secure digital journeys at scale

Our Presence

Leave behind fragmented tools. Stop fraud rings, cut false declines, and deliver secure digital journeys at scale

Our Presence