Guide

Introduction

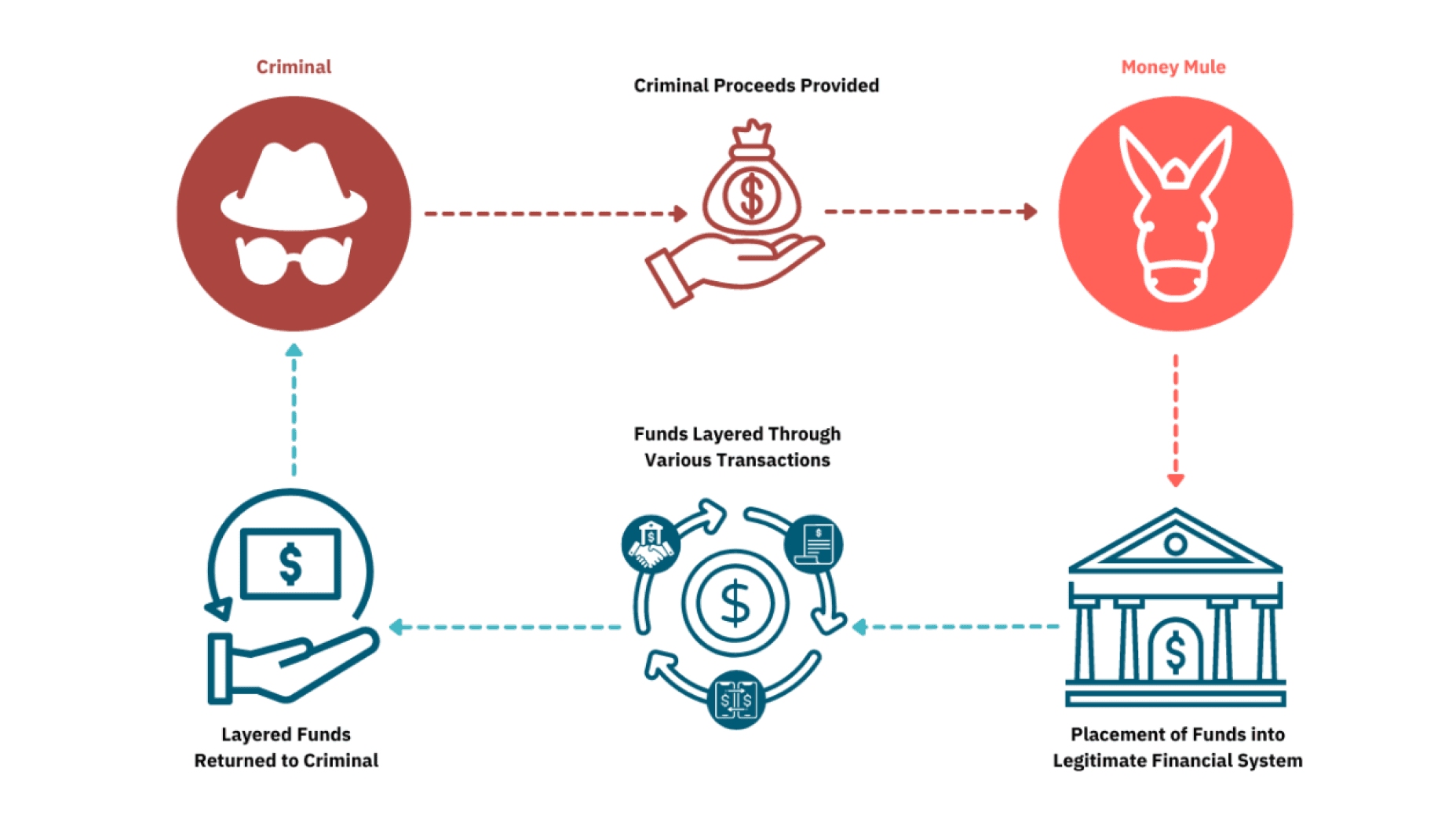

Money mules are individuals who, knowingly or unknowingly, assist movement of funds on behalf of someone else. In recent times, money mule operations have evolved into large, coordinated fraud ecosystems that enable a wide range of fraudulent activities, financial crimes, and money laundering at scale. This poses a direct threat to the integrity of financial systems and exposes businesses to greater operational and regulatory burden.

Not only is the money mule problem all pervasive, it is also costly. It disrupts operations, erodes customer trust, and increases the risks of non-compliance. The interconnected nature of money mule activity can make a single compromised account the launchpad of sophisticated criminal activities across multiple industries and jurisdictions. Therefore, digital businesses find it hard to mitigate financial damages while also investing in strategies that can detect and disrupt mule operations before they can scale.

What is a money mule

According to the FBI, a money mule is an individual who moves illegal money for someone else. Europol considers a money mule as a person who receives money in a bank account, retains a portion of this and moves it onward either through cash transfers, gift cards, prepaid cards, cryptocurrency, wire transfer, or cashier’s checks.

Money mules are treated as accomplices in cybercriminal activities, because they help launder illegal money, whether knowingly or unknowingly.

Creation of money mules

There are several ways money mules are created. These include:

Recruitment: Criminal groups “recruit” individuals to act as money mules through fake job offers. They usually target newcomers in a country, students, unemployed people, and those facing financial difficulties. “Recruiters” may contact the targets directly through email or use social media platforms, community forums, instant messaging, or chat apps. They even provide the “recruits” with step-by-step instructions on opening new accounts or using existing accounts, and pay them using several payment arrangements, such as pay-per-transfer, per account, or per successful cash-out.

Willing individuals: Some individuals knowingly open new accounts or rent out their existing accounts for money mule activities. These complicit individuals test bank defense mechanisms with small transfers, and gradually scale up the volume and frequency of the transfers. To avoid detection, they rotate SIMs, devices, and IPs. They may even travel to different countries to open new accounts, register fake companies, operate accounts that receive funds from new or lower-level mule accounts, and recruit new mules.

Duped: The third category of mules comprises unwitting people who are tricked into money mule activity through various types of scams, such as:

Work from home: The individual is tasked with the “job” of receiving funds in their bank account and transferring them onward via ACH, wire transfer, or money service businesses.

Reshipping: Also known as parcel scam, here victims are directed to receive parcels at their addresses and then forward them to another location.

Romance: Criminals trap unsuspecting victims and earn their trust before manipulating them into receiving and forwarding funds to unknown people or accounts.

Prize winning: The victim is informed of having won a grand prize or a lottery. Fraudsters then urge them to open an account or share details of an existing account to receive the prize money. This account is then used for money mule activities.

Common myths around money mule activity

Despite the scale of threat that money mules pose, there are several misconceptions that can hinder fraud prevention efforts. These include:

Assumption 1: Money mules exist only in banking.

Reality: Mules exist in fintech, payment, gaming, cryptocurrency, eCommerce, marketplaces, and gig economy platforms as well.

Assumption 2: KYC checks reduce mule risk.

Reality: Use of genuine documents, thin credit files, and synthetic identities can allow first-party mules to pass KYC checks.

Assumption 3: Mules can be caught at onboarding or account initiation.

Reality: Most mules pass onboarding because they look legitimate in isolation. The real signal is in who they are linked to, which is invisible to traditional checks.

Assumption 4: Mules act alone.

Reality: Mule fraud is networked, not individual. These accounts are often part of organized rings, using shared infrastructure and playbooks to avoid detection.

Assumption 5: Risk lies within the bank’s own ecosystem.

Reality: Only about 30% of mule activity is internal. The remaining 70% happens outside, in other banks, neobanks, and digital wallets.

Assumption 6: Offboarding a mule account ends the risk.

Reality: Offboarding one account does not impact the active connected nodes, as mules can be replaced quickly.

Assumption 7: Device fingerprinting alone can catch mules.

Reality: Although device signals reduce some risks, mules can still evade detection by rotating hardware and using spoofing tools.

The networked nature of money mule activity

Money mule activity does not occur in isolation. Interconnected networks, comprising individuals, devices, accounts, and intermediaries collaborate to move illicit funds. They operate across jurisdictions and leverage layered account structures to obscure the origin of these funds.

Often, mule networks overlap with other criminal networks, such as fraud rings involved in identity theft, phishing, or synthetic identities syndicates. This interconnected nature of the fraud ecosystem makes dismantling the entire operation difficult, even if a mule account is detected.

Money mule networks follow the hub and spoke model

Money mule networks follow the hub-and-spoke model to operate, where the recruiter acts as the hub and the first-line mules form the spokes. All the scripts, cash-out plans, and cash pick-ups are handled by the recruiters at the hub. The spokes manage local banking access, sub-mules if any, and cash pick-ups. Then there are the co-ordinators who handle cross-border fund transfers, accounts rotation, and implement plans to move money through target institutions.

The transactions are distributed across nodes in the network to make it harder for an individual business or entity to detect mule activity on its own. Furthermore, members are frequently added or removed from the network who shift between banking channels, payment platforms, and jurisdictions to exploit the gaps in defense mechanisms and avoid detection.

Global mule networks leverage a combination of online and offline methods to operate. For instance, digital operations include phishing kits, fraudulent job sites, romance scam scripts, SIM farms, and movement of funds between banks, fintechs, and cryptocurrencies. The offline operations include ATM withdrawals, cash couriers, and drop locations.

How generative AI is compounding the money mule problem

Generative AI is reducing the costs of recruitment and evasion. At the same time, with techniques such as deepfakes, voice cloning, and AI-written messages for phishing, it is helping fraudsters scale up their activities.

Some of the ways generative AI is compounding the money mule problem are:

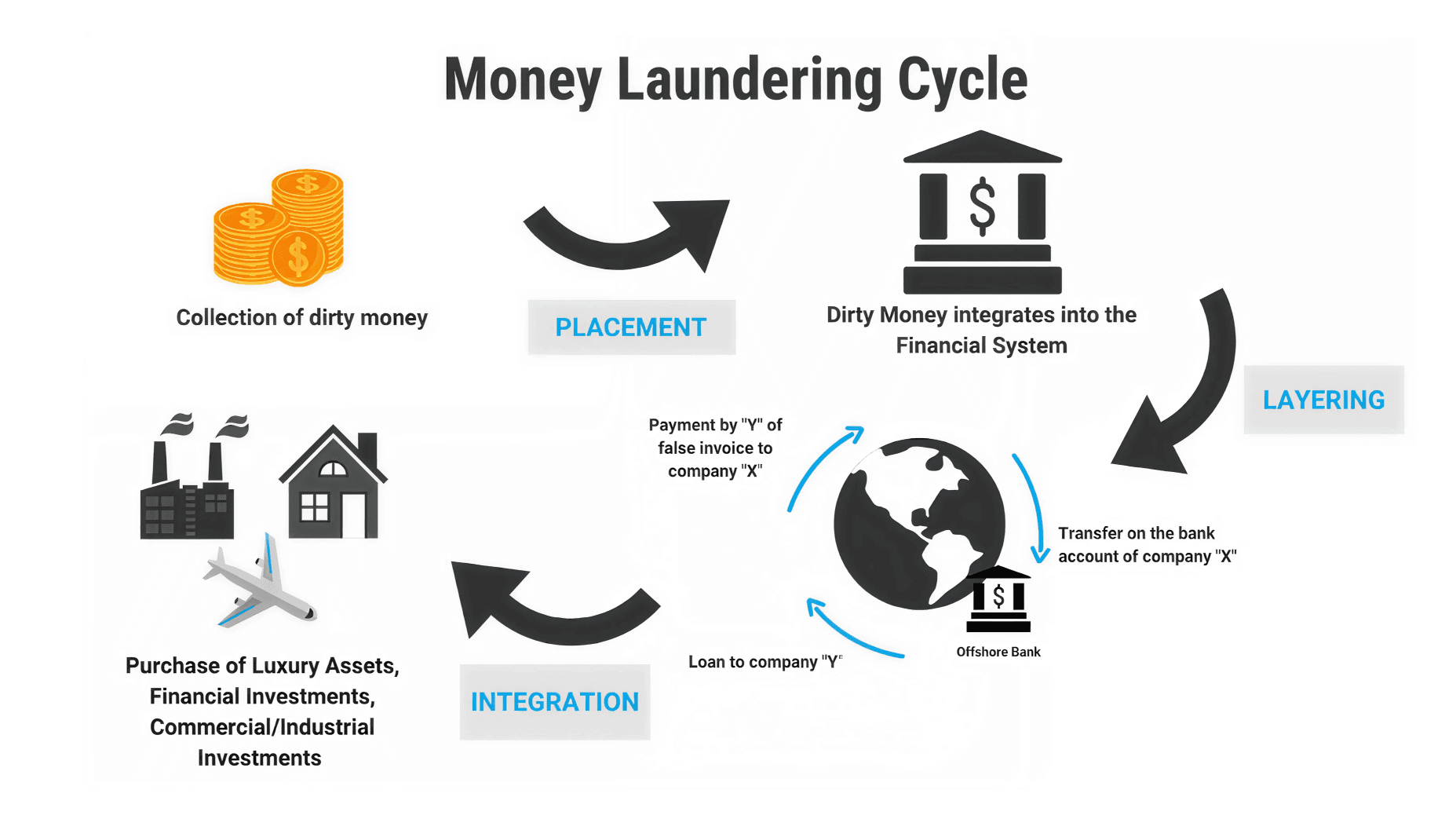

Obscuring the origin of funds: Use advanced AI algorithms to automate and optimize processes for manipulating the origin of funds.

Money laundering: Replicate legitimate financial transactions and break larger transfers into smaller distributed transactions across numerous accounts to launder money.

Simulating business activities: Create fake IDs and documents for shell companies, including synthetic identities, fake invoices, contracts, and other official documents.

Manipulating crypto trading: Mask money laundering activities under the guise of legitimate trading in cryptocurrency.

Creating convincing phishing messages: Create realistic emails and text messages, without the obvious mistakes, for targeted phishing campaigns.

Imposter verification: Using deepfakes, altered selfies, and cloned voices, to open new accounts and bypass weak liveness or callback checks.

The scale of money mule problem

Money mule activity is now a transnational threat. Mule networks operate across jurisdictions, exploiting differences in payment rails, regulations, and enforcement to move funds through banks, fintechs, and crypto platforms. This underscores the scale of AML in banking and the threat that organized money mule syndicates pose.

In the United States, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) identifies thousands of money mule incidents, with fraud losses amounting to billions of dollars every year. European Money Mule Action, an initiative of Europol, co-ordinates with law enforcement agencies from several countries to identify and arrest thousands of mules, saving millions of Euros in losses, annually.

In the Asia-Pacific region, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), Australia’s financial intelligence agency, AUSTRAC, and authorities in India continue to arrest thousands of suspected mule accounts linked to organized crime rings every year. In the UK, money mule recruitment is rising with several teenagers and people under 30, reported to have been coerced into money laundering activities by crime rings. AUSTRAC also warns of industrial-scale mule recruitment of students and migrants in scam syndicates. These trends not only highlight the financial aspect of money mule activity, but also the manipulation of individuals at scale, lowering trust in payment systems, and the borderless nature of organized crime.

Industries most affected by money mules

The rapid growth in digital transactions and cross-border payments is enabling money mules to exploit gaps in fraud prevention techniques. This also allows them to target industries with high transaction volumes, diverse customer profiles, and faster fund movements, as this makes detection more challenging. Here’s how money mule activity impacts various industries:

Banking and Financial Services: From low-value, high volume transactions to complex and layered transactions, banks probably face the bulk of mule activity for money laundering. The challenge further worsens with mules working across jurisdictions and exploiting regulatory differences. Being part of a highly regulated industry, banks and financial institutions must identify and dismantle mule activity, as failure to do so can damage their reputation and increase KYC and AML compliance costs.

eCommerce and Marketplaces: Mule activity exposes these platforms to chargebacks, higher fraud insurance premiums, and loss of buyer and seller trust. Multinational platforms are at a higher risk of cross-border mule activity.

Crypto exchanges: Due to the speed and anonymity of transactions, crypto exchanges are used to obscure the origin of funds by moving them to crypto wallets and then converting them to different currencies. Money mules operate between regulated and deregulated exchanges to evade detection.

Gig economy platforms: Fake driver or worker accounts act as mule accounts to receive funds disguised as payment for the services. In some cases, legitimate workers are recruited as mules through fraudulent job offers. Platforms that facilitate daily or weekly pay-outs are at a higher risk due to faster cash-out, resulting in higher operating costs, risk of payment system abuse, and reputational damage.

Social media and online dating platforms: Serve as a hub of romance scams to trick people into becoming money mules. The ease of creating profiles, global reach of the platforms, and the ability to create fresh identities if one account is blocked, makes these platforms attractive for money mule activity.

Online gaming: High transaction volumes, global reach, and anonymity of online gaming platforms provide money mules with a perfect channel for money laundering activities. Criminals recruit mules who convert illicit funds into in-game currency or assets, reselling them for cash, and using stolen payment credentials to buy credits and request refunds.

Impact of money mule activity

The impact of money mule activity extends far beyond financial damage for businesses, to powering organized crime and fraud networks. Money mule activity impacts both businesses and consumers in the following ways:

Impact on businesses:

Financial: Businesses face direct financial losses in the form of fraudulent credits, refunds, chargebacks, and unrecovered transferred funds. For faster payment rails, write-offs increase with the passage of recovery windows. In addition, businesses incur indirect costs such as increased customer support, third-party investigations, and legal action. Non-recovery of funds from mules, higher insurance costs, and liabilities when mules are caught at other organizations, add to the financial losses.

Operational: As teams investigate suspicious accounts, manage cross-border requests, and file reports, case volumes begin growing. With linked accounts getting reactivated, fraud operations teams must also handle recurring escalations. In parallel, engineering teams iterate existing rules or roll out new ones and tweak ML features to track device resets, SIM changes, and beneficiary rotation. While the risk, compliance, legal, and support teams closely collaborate, post-incident audits can result in stricter rules that can degrade overall user experience.

Reputational: Increased scrutiny from customers, partners, regulators, and investors, along with adverse media coverage can reduce customer acquisition and partner onboarding. Sales cycles get affected due to additional due diligence measures from prospective clients who may place additional safety requirements. Negative stories can quickly spread on community forums and social platforms, leading to an adverse impact on attracting and retaining talent.

Regulatory: Money mule incidents lead to greater regulatory attention, particularly under AML regulations and CTF (counter-terrorist financing) laws. Businesses are required to adopt stronger detection and reporting mechanisms in order to stop illicit fund movements. Failure to comply can result in penalties, such as heavy fines, sanctions, and in worst cases operational restrictions. The requirements are more stringent for cross-border cases, where businesses must report promptly and work closely with the enforcement agencies. In some cases, regulators may mandate retrospective reviews of past transactions, which can impact resource allocation, and ultimately business growth.

Impact on Customers

Money mule activity ultimately affects the end consumers, and they may:

Face risk of physical violence and coercion: Recruiters may threaten individuals of harm to ensure they comply or remain silent, preventing individuals from reporting to law enforcement agencies due to fear of retaliation.

May lose social benefits: Being identified as a mule can result in benefit payments being reviewed or frozen. Accounts may be blocked, impacting access to subsidies, welfare funds, or pensions. Account and identity restoration may require extensive investigations, documentation, time, and effort, which can leave individuals in financial distress.

Face account closure: Banks and fintechs may permanently close the accounts and ban them from opening new accounts. Due to consortium data marking these individuals as mules, they may face difficulty re-entering mainstream banking, increasing the risk of financial exclusion.

Not be able to open lines of credit: Identification as a mule can limit their ability to access credit. Lenders may reject their applications based on the records and shared alerts. Thin-file customers or those with no credit histories may face longer wait periods, be offered unfair terms including higher interest rates or lower limits. For credit cards, issuers may decline new cards, freeze existing cards, block the transactions, or reduce the limits, weakening their credit scores. Similarly students identified as money mules may have their educational loans cancelled and universities may restrict campus jobs for them. International students may face visa complications and fee payments through flagged accounts may be put on hold, disrupting graduation plans.

Be arrested: Individuals may face questioning, device checks, and data collection from the concerned authorities. Law enforcement agencies may impose fines, seizures, travel restrictions, and civil recovery to reclaim the funds lost by victims. In some cases, mules may be arrested or the Court may order restitution along with fines or probation. Failure to pay the fines may result in wage garnishment, further legal action, restricted employment opportunities, and difficulties in long-term financial planning.

How to detect money mule activity

To detect money mule activity, businesses need unified analysis of device, identity, behavior, and transaction flow patterns. This would require them to track sender-beneficiary links, any spikes in transaction frequencies, and fan-in/fan-out movements across accounts, devices, and IPs. The investigations should also include connecting the onboarding signals with account behavior and beneficiary history.

Additionally, businesses must use detection models that can help identify a beneficiary repeatedly receiving funds from multiple unrelated senders, cash withdrawals immediately after credits, payroll descriptions that do not match the user’s profile, transactions timed with wage cycles, and circular movement of funds through exchanges.

Tell tales to be aware of

Mule activity can provide subtle warning signs in transaction patterns, account behavior, and linked identities. Businesses can use these indicators to inform preventive action. Some common signs include:

First credit and instant withdrawal: Receiving first credit from unrelated senders within a few hours of KYC pass, followed by an instantaneous onward transfer or cash withdrawal.

Unusual transactions and timing: Irregular deposits and withdrawals within a short span of time. Initial low value credits that quickly ramp up to larger values. Transactions clustered around nights or weekends.

Large financial transactions: Transferring large amounts of money on a regular basis.

Mismatch between wages and profiles: Narratives for salary or invoices are inconsistent with the profile, or funds are received from various geographic locations without declared reasons.

Higher spending/extravagant purchases: Significant increase in purchase of high-value items.

Risky jurisdictions: Transactions and transfers to risky locations, known for weak KYC AML checks.

Shared devices/IPs: Multiple accounts sharing the same device fingerprint, OS build, emulators, and IPs mapping to hosting, VPNs, or mobile proxies.

Hesitation in KYC: Reservations in updating KYC information for verification purposes.

Best practices to prevent money mule activity

For effective prevention of money mule activity, businesses must follow best practices as described below:

Strong KYC/KYB: Verify individuals and businesses to check for duplicates across names, addresses, emails, phone numbers, documents, and devices.

Device checks: Detect rooted or jailbroken devices, use of emulators or virtual machines, tampered sensors, and link devices to identities.

Beneficiary scoring: Use graphs to analyze transaction patterns, speed, and re-use across organizations.

Limiting new activity: Consider slowing down new accounts or beneficiaries by placing adequate checks and measures before the first payouts or large transfers.

Transfer note scanning: Scan payment notes to detect suspicious or repetitive narratives, linked to known fraudulent activities.

Risk-based holds: Depending on the risk score, adjust the funds hold time.

Cluster removal: Swiftly remove linked mule clusters to cut-off their activities.

Collaboration: Share intelligence with peers and partners. Act on the alerts from law enforcement agencies.

Filing: Report suspicious activity to concerned authorities, maintain audit trails, and ensure compliance with the applicable laws and regulations.

Solutions and techniques that can help fight mules

The sophisticated and networked mule activity requires equally advanced detection and prevention measures that can identify cross-organization linkages to disrupt collusion at scale. Traditional rule-based systems are not capable of detecting evolving attack tactics, such as synthetic identities, layered transaction patterns, and use of advanced AI tools to automate and optimize attack processes. Some techniques that can help counter money mule networks include:

Graph-based link analysis: Allows linking accounts, devices, IPs, and other digital intelligence to uncover hidden mule networks. Because crime networks operate in clusters, account interactions often deviate from genuine customer behaviors. Link analysis can help detect these anomalies even when mule accounts move across organizations and geographical locations; and initiate appropriate interventions before suspicious activities can escalate.

Behavioral biometrics: Helps build behavioral signatures by capturing patterns of how users interact with devices. Inconsistent and anomalous interaction patterns, such as typing speed, mouse movement, device orientation, and scroll patterns, are used to identify mule activity. When combined with other signals such as device, identity, and IPs, behavioral biometrics can help identify mules across multiple accounts.

Device intelligence: Helps businesses detect shared, spoofed, and rooted/jailbroken devices. Also identifies suspicious activities including successive logins across multiple devices, to inform decisions of blocking or further reviewing suspicious users.

KYC: Mules often target weak verification processes; therefore, strong KYC checks and in-platform monitoring can help fight mule activity more efficiently. Businesses can verify documents against reliable databases, match biometric inputs, and validate data to ensure the users are actually who they say they are.

Transaction monitoring: Machine learning models can track and stop transactions with suspicious flows, values, and frequencies, in real time. Unlike static rules, AI-powered models are adaptive to changing mule tactics. This enables them to use contexts like transaction history and network links to flag risky cases for further review and remediation.

Shared intelligence: Mules operate undetected across organizations, as inter-organizational visibility into fraudulent activities is limited. By sharing anonymized intelligence on known mule accounts, devices, and other identifiers through data-sharing platforms and industry forums, businesses can strengthen their collective response. This shared threat intel can improve detection and prevention capabilities across organizations and make it harder for mules to recycle their assets.

Why choose Bureau’s GIN

Bureau's Graph Identity Network framework transforms fraud detection from isolated rule-based checks into a connected, intelligent network. Its tiered architecture ensures that institutions can start with plug-and-play models and scale up to graph-based intelligence, enabling early fraud interdiction, fewer false positives, and deeper risk visibility across the customer lifecycle. It is built to adapt to an organization’s data maturity and risk sophistication with a three-stage mule risk framework. This layered approach allows quick deployment and progressively deeper intelligence.

With ML-based scoring that uses L1/L2 links, Bureau’s GIN can flag fraud in real-time during onboarding and transactions. Because it is trained on actual mule labels and not proxy risk, it delivers sharp interdiction with the top 10% scores precisely detecting 100% mules. It is also privacy-centered with over 1 billion fully encrypted identities.

Bureau GIN uncovers hidden links between seemingly unrelated signals, including collusive users, accounts, devices, behavioral patterns, and more, to help businesses detect and stop mule activity across organizations and geographies. It uses real-time scoring to apply holds, step-ups, and beneficiary checks, as and when needed. Its graph-native features help track mule lifecycle stages, recruiter influence, and interconnected accounts, allowing businesses to dismantle complete mule networks, instead of just closing one mule account at a time.